A stellar partnership

In Chile’s Atacama Desert – 1,000 km of the driest desert on the planet – sit some of the most advanced telescopes in the world. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the remoteness of this locale, an impressive cadre of astronomers from around the globe flock to secure just a few hours on telescopes which can propel their research for months or even years.

Notre Dame physics professor J. Christopher Howk is one such astronomer. He spent 2017 on sabbatical at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) and had rare access to some of the many telescopes. Howk’s research focuses on the role of gas in star and galaxy formation, and how that contributes to the evolution of the universe.

“In large part, the gas we’re interested in is pretty much invisible because it’s at such low densities that it doesn’t give off much light itself. What we do, is we look for the fingerprint that it leaves on the light coming from items that are very far in the background,” he explains. “Objects like quasars, which are prodigious producers of light, we can look at them and as light passes from the quasar to us, if it passes through gas, that gas will leave its fingerprint on the light that we see.”

“It’s sort of like doing analytical chemistry in the sky,” he summarizes.

During his time in Chile, though, he says he pulled away from his normal research, and instead focused on opening his aperture to new questions and ideas from his Chilean colleagues.

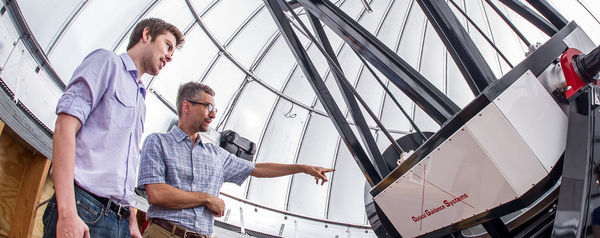

Professor Howk with a graduate student in the observatory

Professor Howk with a graduate student in the observatory

“Part of the reason for going to Chile is yes, they have Very Large Telescopes there. But also, because of the investments the Chileans have made over the years, they have a vibrant community of astronomers who are doing interesting work,” he says.

In the 1950s, European and American observatories began investing in large, ground-based telescopes in Chile’s desert because of the ideal conditions – dry, high altitude, cloudless, reduced atmospheric effects – for astronomical observances. In suit, Chile created incentives, including research funds at universities and minimum quotas for Chilean researchers on the telescopes. The continued investments, infrastructure and technology have made Chile a hub for astronomers of differing interests. That variety of ideas and trajectories, Howk says, has been reinvigorating for his own research.

“Part of your development of ideas is from interacting with people and learning from them. For me it was a new environment, a different environment, one that was stimulating,” he says. “What we do requires that we be creative and be open to new ideas and have a sharp mind about all that. Stepping away from the daily administrative tasks, and oversight tasks, and department, and the teaching to some degree, and interacting with a new group of people, refreshed my mind.”

That’s not to say his sabbatical was a solo mission. Since 2013, Notre Dame has worked to strengthen ties with PUC through collaborations and exchanges across disciplines. One valuable resource for faculty who wish to network there is the Luksburg Foundation Collaboration Grant, formerly the Luksic Grant, presented by Notre Dame International and the Kellogg Institute for International Studies. The grant, which was announced as a five-year provision in 2017, awards up to $20,000 to individuals or research groups to support exchanges with PUC.

“What I appreciate about the Luksburg grant, and the two universities making this a priority to make connections, is that it allows us to do more than just travel to Chile in order to use telescopes. It allows us to actually interact with the Chilean community and develop ties that not all universities and research groups have.”

Howk notes that a typical researcher visit to an observatory like the ones in Chile is all-inclusive. Observatory employees arrange the travel and cars and meals, so a researcher need not ever actually engage with Chileans. But his sabbatical allowed him and his family to fully immerse, a challenge which reaped immense rewards, he says.

“What I really appreciate about what we’re doing is that we’re stepping outside that bubble as it were, and we’re really trying to engage Chilean astronomical community. That in turn, is really encouraging the development of scientific ideas and capabilities with the Chilean community as a whole.”<

Notre Dame is also welcoming the Chilean community to South Bend, Howk notes. This academic year, Alejandro Clocchiatti, a professor at PUC will teach at Notre Dame alongside Howk and Timothy Beers, the chair in astrophysics.

“We see this as the start of faculty and student exchanges,” Howk says.

The relationship between Notre Dame and PUC affords great benefits for students as well. Discussions are underway to create dual-degrees and exchanges for graduate students and post-docs, Howk says. And even some undergraduates have found research opportunities while in Chile.

Erik Peterson at the European Southern Observatory

Erik Peterson at the European Southern Observatory

Erik Peterson, a senior physics student, was able to complete three credits of research at the Institute of Astrophysics at PUC while studying abroad in Santiago during the spring 2018 semester, thanks to a relationship between his research advisor at Notre Dame and a colleague at PUC.

In the Chilean lab, he says he worked closely with a master’s student who was looking for possible triple stars in a catalog of binary stars. Though much of that research is computer programming, he says, he was also offered the opportunity to go to the European Southern Observatory, the home of some of the most advanced telescopes. But a shift at the observatory isn’t what it might seem, he says.

“Contrary to popular belief, an observing night is not looking through the telescope peeking at the stars. What we did, is you go into a control room, which is a quarter mile from the telescopes. I counted 18 computer screens up, and they’re working on all the instruments,” he says. “They essentially are taking pictures with super long exposures to gather all this light. From that light, they can get all kinds of information.” That information can help scientists understand everything from how fast a star is moving to if there’s potential for new planets.

Though his particular shift on a smaller, 1-meter telescope, involved mostly properly aiming the telescope via his computer, Peterson was enthralled. The experience solidified his decision to pursue an advanced degree in astrophysics. It also gives him a unique story to share and an international recommendation letter on his graduate school applications, he says.